Channel Conflict and the Politics of Direct-to-Consumer

In 2003, selling direct was an act of rebellion inside a wholesale company.

Nike had spent decades building relationships with retailers. Foot Locker, Dick's, Finish Line—these weren't just customers. They were partners. They carried the brand into malls, ran local marketing, and bought in volumes that made planning predictable.

Direct-to-consumer threatened that entire machine.

If Nike sold direct, would retailers reduce orders?

If pricing was transparent online, would international distributors lose margin?

If inventory was allocated to DTC, would retail partners stock out?

These were not abstract questions. They were weekly debates in conference rooms.

And I was in the middle of them, watching grown adults with impressive titles struggle to reconcile two contradictory truths:

Direct was inevitable. And direct was dangerous.

**The Two Religions**

Inside the company, two factions emerged.

The first believed DTC was the future. Cut out the middleman. Own the customer relationship. Capture the margin. This group pointed to every other industry where disintermediation had already happened. Books. Music. Travel. Why not footwear?

The second believed DTC was suicide. Retailers would retaliate. Shelf space would shrink. The brand would lose cultural penetration. This group had spreadsheets showing what happened when a major athletic brand alienated Foot Locker in the 1990s. It was not pretty.

Both sides were right.

That was the problem.

**What I Learned Watching the Battle**

I was not senior enough to have a vote in these debates. But I was senior enough to see how they actually got resolved.

Not through strategy. Through economics.

The question was not whether DTC was good or bad. The question was whether the wholesale channel would actually retaliate, and if so, how much it would cost.

That required answering harder questions:

What percentage of Nike's revenue came from each retailer?

How substitutable was that revenue?

What would a 10 percent reduction in wholesale orders do to factory utilization?

Could direct growth offset wholesale decline within a reasonable timeframe?

These were not marketing questions. They were not technology questions. They were capital allocation questions.

And they had no easy answers.

**The Fragile Compromise**

What emerged was not a strategy. It was a series of compromises:

DTC would exist, but it would not compete on price.

Assortments would be differentiated, not duplicative.

Inventory would be allocated to protect key retail partners.

Direct would be positioned as "brand experience," not discount channel.

These compromises satisfied no one completely. But they allowed movement.

That pattern has repeated in every channel conflict I've witnessed since:

Book publishers and Amazon.

Hotels and Expedia.

Manufacturers and their own distributors.

The conflict never resolves. It just evolves into a new equilibrium.

**What I Carried Forward**

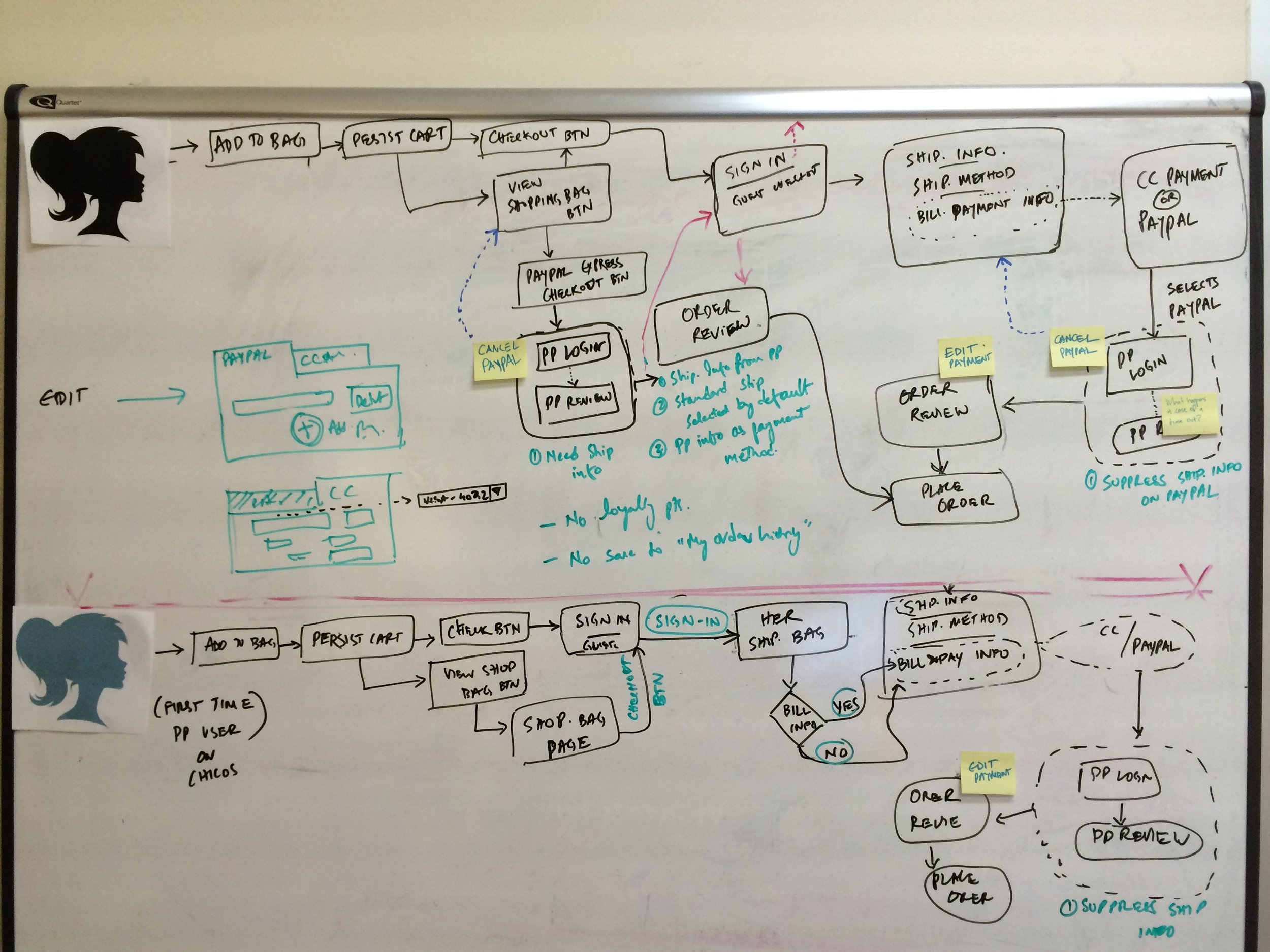

At Chico's, I watched the same tension play out between stores and ecommerce. Store managers were compensated on store revenue. When customers bought online and returned in store, the store bore the cost but got no credit. The conflict was baked into the incentive structure.

We fixed the incentives before we fixed anything else.

At JCPenney, BOPIS seemed simple until we realized store associates had no idea how to process online returns. The training hadn't been updated. The systems didn't talk to each other. The economics of returns were worse than we'd modeled.

We fixed the operations before we marketed the promise.

At SelectBlinds, we were pure DTC, so channel conflict wasn't external. But it existed internally: between manufacturing and sales, between marketing and operations, between the teams that wanted to grow fast and the teams that had to deliver.

The lesson from Nike applied just as well:

Economics always wins arguments.

If you want to resolve conflict, don't appeal to vision. Appeal to incentives.

**What I Understand Now**

Looking back, the DTC debate at Nike was never really about DTC.

It was about power.

Who controls the customer relationship?

Who captures the margin?

Who decides how the brand appears in the world?

Those questions never go away. They just shift to new terrain.

In 2026, the same debate is happening around AI platforms, around data ownership, around marketplace control. The players are different. The dynamics are identical.

Incumbents protect what they have.

Challengers want what they don't.

The outcome is determined not by who is right, but by whose economics are more durable.

**For Recruiters and Boards**

If you're looking for a CEO who understands that strategy is not about declaring winners—it's about managing tension until a new equilibrium emerges—I'd welcome the conversation.

I learned that inside Nike, two decades ago.

I've been practicing it ever since.